Source: 2024 Q4 Beartracks, Greg Charest

After investing a lot of time and money, your shiny new Bearhawk is complete and has a special airworthiness certificate. You have taken transition training, made decisions about insurance and your first flight was a success. Fantastic! You are officially in Phase 1 Testing. But what now?

As you probably know, the FAA allows two different approaches to Phase 1 testing:

1) You can operate the aircraft within a designated area for some number of hours (usually 25 or 40) with some number of takeoffs and landings (generally 10 or 20) to complete Phase 1. These limits are specified in the Operating Limitations that accompany your Airworthiness Certificate.

2) Alternatively, you can use the Task-Based Approach to testing outlined in Advisory Circular (AC) 90-89C. This program was developed in cooperation between the FAA and EAA. It outlines 21 different test areas and associated test cards that can be used to document the process and results.

There are compelling reasons to use the Task-Based approach, not the least of which is that you would likely do something similar even if you chose to simply fly the 40 hours. After all, you want to know best glide, Vx, Vy, stall speeds, effects of various flaps settings and so on. Why not take advantage of the structured approach and do it in a methodical manner? As a side benefit, it may be possible to complete Phase 1 in a shorter period as the requirement is to develop and carry out a plan, not meet an arbitrary time goal.

It’s important to keep in mind that the Task Based Approach is FAA guidance, not a set of regulatory requirements. It is intended to help you develop an individualized plan. The related EAA Flight Test Manual is a concrete example of a task-based plan. You can and should feel free to create a plan that meets your needs. While the EAA documents are quite good you may want to include other tools in your plan. For example, The Bootstrap Approach to Aircraft Performance by John T Lowry is an excellent alternative to help calculating V speeds and rates and angles of climb/decent. See Jared Yates’ article in KITPLANES magazine for a review and explanation.

While the task-based approach is superior, there are some practical difficulties in completing the tests. The most significant issue is that there is often a lot to do at the same time. Precise flying, monitoring engine data, watching for traffic and collecting the required performance data can be a lot to manage by yourself. This is especially true if, like the typical builder, you have spent a lot more time building than flying in the last couple of years and are a little rusty.

There are a couple of ways to make the testing process a little easier and to generate better test data. One is human-related and the other technological. The human solution is to use the Additional Pilot Program for Phase I Flight Test Program described in Advisory Circular 90-116. Note that this only applies to aircraft built from commercially produced kits. Operating limitations issued for Phase I operations restrict the number on board an aircraft to the minimum flight crew. In general, the minimum crew for a typical E-AB aircraft is one (you). AC 90-116 provides a mechanism that allows you to have a second pilot on board to assist in the testing process. It defines two categories of pilots approved to assist: Qualified Pilots (QP) and Observer Pilots (OP). Qualified pilots can participate immediately but the QP experience qualifications are quite high (see 90-116 for the specifics). Observer pilot qualifications are lower, but you must complete the first 8 hours of testing, including a specific set of tests and maneuvers, before you can use an observer pilot. If you want to have another pilot assist you, it makes sense to modify your test plan to meet these requirements early on.

The technological solution works if your airplane has an EFIS. Most if not all EFIS systems are able to write data to a log file. The Garmin G3X for example logs 81 data elements every second, some are direct measurements, and some are calculated values. These are written in a standard comma separated format. This relieves you from the need to write down key altitudes, airspeeds, times etc. and allows you to focus more on flying the maneuvers, watching for traffic and staying inside your designated testing zone.

There is an amazing amount of useful data in the log file, but it can be overwhelming. A typical test flight will result in a >3000 row spreadsheet. Finding and selecting the relevant records and values can be a challenge. It’s helpful to use the tools provided by whatever spreadsheet program you prefer to reduce the data set. Spending a little time to hide the columns you don’t need and freeze the field name rows is worth the time. More advanced techniques to average some of the measurements may also help to reduce short term variability in the recorded data.

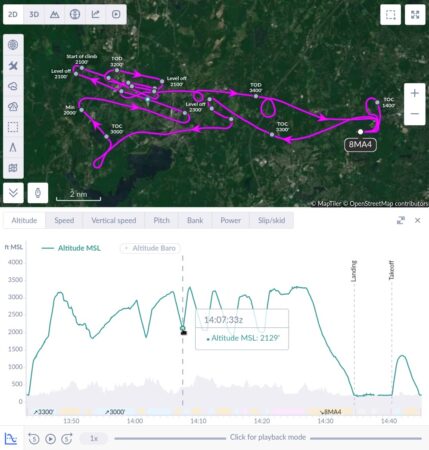

Even after cleaning up the data it can still can be tedious to find the records that correspond to precise start/stop times in such a large data set. This is where the web application at https://www.flysto.net is especially useful. This tool can analyze the log file, separate the flight into parts, map your flight path and plot altitude, speed, pitch, bank etc. Placing your mouse pointer over a specific point on the flight track will display the related time field. This lets you pick a portion of the test flight graphically and directly match it to the corresponding rows in the data. You can see in the example below how straightforward it is to select the exact time elements for the climb/descent portions of the test I was flying. The flysto.net tool is free and has many other useful capabilities.

Flight testing is not easy and can be a little frustrating. Real world data rarely looks as nice as the textbook examples. Hopefully some of these tips can help you get better results and focus on the fun and educational aspects of the Phase 1 process.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.