Spring 2025 Western Backcountry Bearhawk Meetup

Cabin Organization with MOLLE

Source: 2024 Q2 Beartracks, Tyler Williams

I like clean organized spaces. Well, at least I do in my airplane and in my kitchen. My truck, on the other hand, is a complete mess…always. It looks like I live in it, which sometimes I do. But not a lot goes on inside the truck that forces me to be meticulous about it being clean and organized. I sit, hold the wheel, throw the snacks in the center console and turn on some good tunes. My kitchen is a different story. My chef’s knife is sharp, my spices are stocked and I am a stickler for “mis en place.” When everything is in its place, I can work efficiently and get into a flow to create, improvise and make great food.

Operating the airplane is a similar experience for me. I like everything in its place, the plane prepped and my mind sharp for the task at hand. Flying a plane, at least the way I do it, involves much more than road tripping in the truck. I don’t just get in, hold the wheel and follow the line on the map. From the preflight, to the engine management, to flying the terrain and improvising the route around weather and airspace, to chatting with ATC and jotting down instructions, there’s always something to do. An organized cockpit helps keep the mind free for the important things, and I don’t like anything flopping around loose. When flying far, I need water, a bag of snacks, sometimes a pen and paper, sometimes I need my flashlight, I’ve got my InReach on and I like to plug in my phone for music. I keep a lot of stuff in the back of the airplane too and it all needs a secure place to rest. From the basic things like a screwdriver, fuel tester and a small flashlight that get used every preflight, to the just-in-case tool kit, spare fasteners, tubes and patches, to control locks, tie downs, travel chocks and a first aid kit, I like to have what I need, when I need it. You can usually find help anywhere in the lower 48, but it sure is nice to have what you need to handle things, in flight and on the ground.

When I finished the Bearhawk and started venturing across state lines, I kept all the tool kits and spares in a duffel bag in the baggage area. But, digging through a bag of stuff to find what you can be annoying at best. For the cockpit items, I initially used the side pockets installed by my feet and the seat back pockets to stow checklists, small items, snacks and water bottles. But we travel as a family often and I like to keep those seat back pockets clear for my kids to stow their drawing paper, books, cards and such. My side pocket is best kept minimal so I can get my checklist or writing pad without fumbling around down there while trying to fly and my wife likes to have her side available for her magazine or book.

I got some inspiration from some nice overland camper trucks that used the MOLLE (Modular Lightweight Load-carrying Equipment) system to organize gear and tools. I saw seat-back MOLLE panels with small pouches and also some nice tailgate MOLLE panels for easy access to tools, even when the truck is loaded with gear. That seemed like the perfect solution for my plane. Our doors are all recessed slightly from the interior so there’s a little space there that can be used to hang a MOLLE panel and install some organizers.

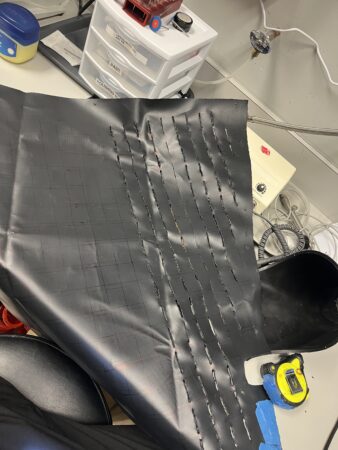

I made mine out of PVC coated Cordura nylon. I found some basic dimensions for the standard laser-cut Molle grid, drew it out on the fabric and simply melted the slits with a soldering iron. Mine are 1.12” wide slits, spaced ¼” apart horizontally and 1” apart vertically. I probably don’t have the exact military spec, but it was easy to lay out and fits all the attachments well. Someone more digital savvy could do the layout on a computer and have the fabric laser cut for a faster and more precise, factory looking result. I installed snaps in the door frames and fabric and snapped on the panels. They are lightweight and work great. Up front, I have my water bottle holder, sunglasses, pen, charge cord pouch, a place to keep my phone and snacks and my fire extinguisher secured on the door for easy access and still have all the elbow room I need. The passenger door has a panel as well with the same drink holder and stuff pouches and my wife loves it. The big panel on the aft baggage door stores my first aid kit, gust locks, travel chocks, extra quart of oil and funnel, preflight tools, hanging luggage scale, spare fuel cap, pitot cover, etc. etc. You can certainly stuff all these things under the back seat and that works just fine. But it sure is nice when the plane is fully loaded to be able to just pop the baggage door open and grab what you need.

Bearhawk Camping at Creighton Island, Georgia

Source: 2024 Q2 Beartracks, Tyler Williams

“So, is there anywhere to go around here where you need a plane like that with those big tires?” This is the most common question I get from the classic plane peepers at the fuel pumps. And I don’t even have real Bushwheels yet. The Bearhawk draws a lot of attention. It is a cool looking airplane compared to the flock of sheep on the ramp. Just looking at it conjures up thoughts of adventures far and wide and nights spent under the stars. So, my response is always, “No. Not around here. But I didn’t spend two and a half years building a big, family hauling, off airport capable airplane to stay around here.” Here in the east, the mountains and ocean are several hundred miles apart. I love being in both places and the Bearhawk gives us more access to it all. I live in Charleston, SC, near the ocean and love it. Once in a blue moon, we get some good waves and there’s great salt marsh fishing to be had just a short walk down the street from our home. Charleston is also FULL of people and is lacking in wide open space to get away from it all. But, I can fire up the old Lycoming, load up the family and in an hour or two, we can be saddling up the mountain bikes, or pitching a tent in the grass.

The closest place we can fly into where the people are few and the stars are many is a little barrier island on the Georgia coastline called Creighton Island. It is a short 115 nm flight and though it is close to the mainland, being there feels far away. It isn’t “around here,” but is accessible for us on any good-weather Saturday. Flying along the coast at low altitude is always a treat. We follow miles of waterways, marshland and tidal creeks curling around the barrier islands that dot the entire Carolina and Georgia coast. We dodge pelicans and seagulls, spot dolphins and the occasional shark cruising the beaches. No magenta line is needed for a trip like this.

Creighton Island’s grass strip is supported by volunteers in the Recreational Aviation Foundation and all the info for visiting pilots is in the airfield guide on their website, www.theraf.org. The strip, lined with old growth oaks and palmetto trees, is a fun and fairly easy place to land, with a beautiful approach over the lowcountry marsh. Once in a while, a low pass or two is required to run the animals off the strip before landing. There are no roads out there and the island has been privately owned by one family for several generations. Over time they have made the place an easy place to camp. If you prefer a roof over your head, there are a few hunter’s cabins that have been built out there for the bow hunters who frequent the island for wild hogs. There is good well-water, a big cast-iron fire bowl, an outhouse, and even a weather station to check before you go. This isn’t the backcountry, but it is a beautiful quiet place to get the Bearhawk away from the pavement and spend some time outside with the family. Donkeys, pigs, cows, and armadillos roam free, making my 5 and 7 year old kids feel like they are on some kind of safari of the American South. Plus the fishing is great. Really great. The east side of the island has a little sand causeway out to a small sandy island on the waterway where bald eagles were nesting this past winter. On the other side, there are spartina grass flats that flood at high tide and offer access on foot to sight-fishing for spot tail bass. These fish are super tasty, fun to hunt and fight, and we are always hoping to score a few. If that’s not enough, there’s a boat dock where you can access some deeper water. It is hard to beat pitching a tent under the massive oak trees and Spanish moss, cooking dinner over the fire after a day of fishing, roaming the woods, and flying over a beautiful coastal landscape. It is almost close enough to home to consider it “around here” and we are thankful to have access to such a beautiful spot.

This would be a fun venue for a winter Bearhawk fly-in.

Ken Frahm’s Bearhawk 4-Place – N907KM

Cross-Country Cross Country – Flying from Arizona to Virginia with a Pair of Bearhawks

Comparing the Companion to the Other Man’s Rans

A Bearhawk Time Machine – Flying to a Remote Test Site in California

Source: 2021 Q4 Beartracks, Russ Erb

You’ve heard it before—“Airplanes are Time Machines”. Usually this is in reference to airplanes being faster than other forms of transportation, able to get you to your destination quickly and allow you to get more “stuff” done in a particular time. For the purposes of this discussion, however, I’m thinking more along the lines of H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine, where my Bearhawk Three Sigma took me back in time to a set of events in my Dad’s history that actually took place before I was born. You may have done a similar thing—someone told you about an event of significance that happened in the past. Later you happened to visit the location of said event and tried to imagine what it was like to have been there. But what do you do if the location is essentially inaccessible? To bring you along on this journey of mine, let me first take you back in history to the events in question.

Piasecki H-21C Hover In-Ground Effect Flight Testing

Lee (Dad) and Alice (Mom) had just returned home from their honeymoon in 1954 when my Grandfather (Mom’s Dad), the local letter carrier, handed Dad a letter from the US Air Force telling him it was time to go on active duty to serve his ROTC commitment. He was sent to Edwards Air Force Base to become a Flight Test Engineer (FTE), a job I would later adopt for a full career.

One of the projects he was assigned to was flight test of the Piasecki H-21C Shawnee helicopter, more commonly known as the “Flying Banana”, even though it wasn’t flown by Gru’s minions.

Above: Alice and Lee at the Armed Forces Day Open House, 21 May 1955, standing in front of his H-21C flight test helicopter. Lee is holding my older brother who is two weeks old

Below: Piasecki H-21C Shawnee, powered by a Wright R-1820-103 radial piston engine

One reason helicopter performance testing is different is the strong influence of ground effect. While airplanes do respond to ground effect (better performance within one wingspan of the ground), the effect is not generally that significant. I do takeoffs and landings in my Bearhawk without any noticeable feeling that I have left or entered ground effect. Helicopters, however, are strongly affected

by ground effect, sometimes able to hover a few feet off of the ground in ground effect but unable to climb any higher. This was especially true of older piston engine helicopters, where the power plant weight was high and the payload was very limited. In this case flight could only be established by flying forward in ground effect (or on a runway) until translational lift reduced the power required enough for flight.

Airplanes can generally be tested for predicted takeoff and climb performance at high altitudes simply by doing level accelerations and climbs at higher altitudes, thousands of feet above the ground, because the difference caused by ground effect is so small. For helicopters, this doesn’t work at all, and tests have to be run in ground effect at high density altitudes.

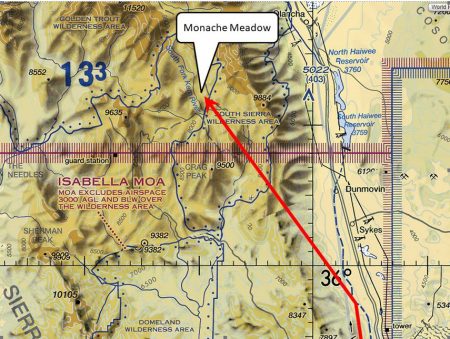

Of course, this requires having a suitable airport, or at least terrain, available for testing at high elevations. The elevation of Edwards AFB is only 2311 feet, which isn’t exactly high. One high altitude site available within a reasonable distance from Edwards AFB is Big Bear Airport at 6752 feet elevation. Big Bear is noted for its ski resorts and alpine climate, as well as Big Bear Lake. Dad said that they did some helicopter testing at the Big Bear Airport. I have even been involved with a flight test project flown at Big Bear to simulate the elevation of the US Air Force Academy. For really high density altitudes they would go to a place called Monache Meadow (type “Monache Meadow California” into Google Maps to see where it is located). This area was well up in the Sierra Nevada mountains with elevations of 7600 feet and higher. There was a large open area without trees or mountain peaks in the way, making it ideal for helicopter testing only 79 miles from the base and inside the MOA/Restricted Area.

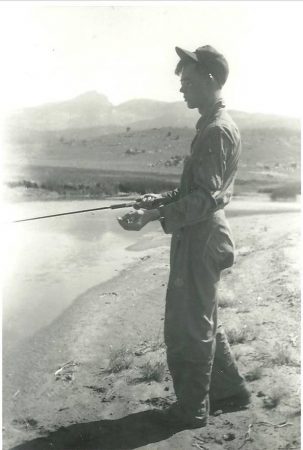

Above: Dad’s Test Pilot, Gus Vincenze, with the H-21C, possibly on Monache Meadow.

Below: Flight Test planning in the field, possibly on Monache Meadow. Lee is in the white coveralls on the right. Then again, they may just be shooting craps…

Below:From his own annotation written on the back of the photo “1/Lt Lee Harvey Erb testing the H-21C helicopter at Monache Meadow, CA. 7600 foot elevation. June 30, 1955”. Note that his first son is less than two months old at this point. This is probably at the South Fork of the Kern River

Dad told me the story that the Air Force was very welcome at Monache Meadow. A man who lived there had a daughter who was very sick and needed to get to a hospital. Unfortunately, Monache Meadow is only accessible by 19.5-mile Monache Meadows Jeep Road that is rated as “moderate” and 4WD recommended—not exactly ambulance accessible. Instead, he called the Air Force requesting assistance. The Air Force sent an H21C up to Monache Meadow, but the density altitude was so high that the helicopter could not take off with the pilot, the patient, and the crew chief on board. Therefore, the crew chief got off the helicopter, and the pilot flew the patient to a hospital. The crew chief waited at Monache Meadow until the pilot could return with the helicopter to retrieve him. Needless to say, the father was very appreciative and gave great support to the Air Force whenever they were there.

Road Blocks In The Space-Time Continuum

My Dad had told me these stories long ago. From several of his visits while I worked at Edwards AFB, I had managed to piece together much of his history in my mind, including locations where he had worked. Part of the problem was that he was at Edwards at the time that Edwards was transitioning from what is now called “South Base” to what is now called “Main Base”. If you look at an airport diagram of KEDW, Chuck Yeager, Jack Ridley, Bob Cardenas, and Bob Hoover did not take off on Runway 23L-5R, the current main runway of Edwards AFB, on 14 October 1947 to break the sound barrier. That runway didn’t exist yet. They took off on Runway 25-7, which at the time was labeled 24-6.

The movie Toward the Unknown was shot around this time and helped with understanding the previous base configuration. I had also flown to Big Bear multiple times, so I knew where that was. Monache Meadow was another problem, though. Dad couldn’t really remember exactly where it was, other than “up north in the mountains”. Adding to the problem was the way he said the name, which sounded like “Menanche Meadows” to me, which didn’t show up on any of the maps (this was before Google Maps). For that matter, it isn’t called out on the sectional or any other aeronautical charts. I often wondered if that was just a nickname for the location, named for someone who lived there and not officially recognized by the US Geological Survey. When Dad passed away in February 2020 I figured

that I would never know.

Somehow recently I stumbled across something that mentioned “Monache” and I wondered if it could be related to what I was looking for. After some Google searching, I found Monache Meadow in about the expected location. It fit the description of a high altitude plain in the mountains within the Edwards flying area, empty of trees and obstacles. As mentioned before, I couldn’t drive there since it was way up in the mountains and I didn’t have a suitable vehicle. I could possibly fly over it, but there were very high peaks around it. I would have to plan carefully and watch out for high terrain and strong winds that could cause turbulence.

Going Back In Time

I asked Aaron, a coworker and student pilot, if he was interested in some Bearhawk flying. He had been waiting for this offer for a long time, and said he was interested in looking at some wooded mountain terrain near Tehachapi for an upcoming project. I agreed, and asked him if he would also be interested in a high altitude overflight of Monache Meadow. He agreed, which was great, because I needed a second crew member to do the overflight safely.

On 20 November 2021 the sky was clear and winds at altitude were light. Flying up the narrow VFR General Aviation corridor between the Sierras and the China Lake Restricted Area, we approached at an altitude of 10,500 feet, which near the mountains still seemed low. Because of the high peaks just East of Monache Meadow, we turned in early over a lower ridge to stay over relatively lower terrain, as shown by the red arrow.

Over the mountains I drifted up toward 11,000 feet as the ground still seemed close. I handed my phone to Aaron and asked him to take “a whole mess o’ pictures” while I made two right hand turns over the meadow. I knew from previous experience that it is dangerous to try to fly turns over a point on the ground at low altitude while looking at that point on the ground and studying it. It’s even worse if you are trying to take pictures of that point on the ground. The problem is that while staring at the ground it is very easy to lose your pitch control, either descending without your knowledge or slowing to a stall. That’s why I had Aaron take the pictures while I divided my attention between maintaining altitude, not running into high terrain, and occasionally glancing at the ground.

While it looks flat and possibly landable from this altitude, I wasn’t interested in biting off that much risk, especially at these high altitudes. It appeared completely deserted. Even so, it was very fulfilling to see the place from altitude. Now I knew where it was, and I could imagine my Dad down there, struggling with an underpowered helicopter trying to collect flight test data for the good of the Air Force. The Bearhawk had taken me there to feel a connection to the work that my Dad had done which inspired me to follow my career. The best part is that I can go back there again.