Source: 2024 Q1 Beartracks, David Swartzendruber

I am building a Bearhawk LSA and one of the engine options for the LSA is a Corvair auto engine conversion. This is what I have chosen for my LSA and I completed my engine build at the end of 2023 during a 3-day supervised build in William Wynne’s shop in Florida. Bob Barrows and William Wynne worked together to design a motor mount for the Corvair engine in the Bearhawk LSA and this mount is available from William. But I’ll back up and start at the beginning of my story.

Like many of you, I decided I wanted to build an airplane many years ago, about 33 years ago for me. However, along the way I lost that dream when it didn’t seem like time or money would allow that to happen. About five years ago, that dream was rekindled when I picked up an unfinished non-Bearhawk project for a very affordable price that was designed to use a VW engine conversion. As I thought about what to do for an engine, I came across the Corvair and William Wynne’s website, Flycorvair.net, and began to consider using a Corvair engine in that project. Through the information on Flycorvair.net, I also discovered the Bearhawk LSA was a good candidate for the Corvair engine and I became less enthusiastic about the project I had acquired. I eventually decided to order a Bearhawk LSA kit and sell the other project.

Having already started down the path of building a Corvair flight engine, I thought I would go ahead and complete that while I waited for my LSA kit to arrive. The first step is to get a conversion manual from William Wynne. This manual includes information about which core engines can be used to build a flight engine. I picked up a 1965 Corvair parts car for $250 and the engine from that car became my core. Corvair flight engines always start with a 1964-1969 engine because engines earlier than that had a smaller stroke, lower displacement and lower strength crank and rods. My core engine was locked up, but I was still able to disassemble it and discovered that the piston rings on one piston had rusted to the cylinder wall. To my surprise, I found that my 1965 engine had a crankshaft and rods from a 1963 or earlier engine. This ended up not making any difference because I decided to go all out and build the bored and stroked version that bumps the displacement up from 164ci to 200ci, also referred to as the 3.3L. The 3.3L engine requires a new billet crank, billet rods, forged pistons and special cylinders so my old crank and rods weren’t needed anyway.

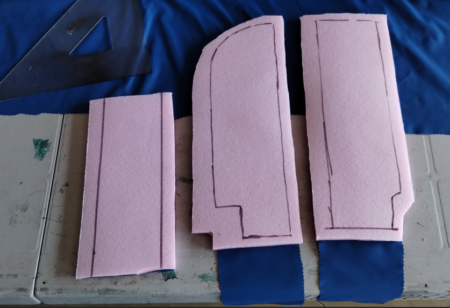

I shipped my engine case and heads off to Sport Performance Aviation (SPA) in Florida for machine work on the case and heads and complete rebuild of the heads. Larger holes are bored into the case to accommodate larger cylinders and some clearance machining is done inside to allow the rods on the stroked crank to clear the case. SPA developed the 3.3L stroker parts, so I bought the new crank, rods, pistons, rings and cylinders from SPA. In addition, SPA has developed a 5th bearing system for the front of the crankshaft to react the propellor loads not normal to an automotive application. All the other standard conversion parts from William Wynne are also used in the 3.3L stroker, so I ordered those from William, including:

-Prop hub, safety shaft and hybrid mounting studs

-Ring gear, starter and aluminum top cover

-Billet aluminum oil pan with oil pickup tube and screen

-Oil filter housing, oil cooler adapter and AERO-Classics oil cooler

-Rebuilt oil case with high volume oil pump

-Rebuilt distributor with Willam’s dual ignition conversion

-Reground camshaft developed by Crane cams for William Wynne

-Alternator mounting bracket

-Modified valve covers to add oil fill tube and vent ports

-Billet aluminum pushrod tubes

-Rotec throttle body injector

-Stainless steel intake and exhaust manifolds

-Engine mount for Bearhawk LSA

-Fiberglass nose bowl

-Engine baffles are coming later but are also offered by William

Once I had all the parts, I began to assemble the engine. The case came back from SPA already closed with the crankshaft, camshaft and 5th bearing installed. This would normally be done at home on the lower displacement engines, but on the stroker motor SPA wants to make sure everything goes together with adequate clearance and rotates freely. I installed the hybrid studs, safety shaft, prop hub and ring gear on the front of the crankshaft and then added the oil case to the rear of the engine.

At this point, I masked things off and painted the engine case and rear oil case. I also cleaned up the new cylinders and painted them. More assembly would have followed from here, but I had decided to take advantage of the supervised engine build opportunity that William Wynne offers. I traveled to Florida with my partially assembled engine and all the other parts and over the course of three days, completed the engine build and test ran it on Williams test stand with a club prop. I liked the idea of spending 3 dedicated days and completing the engine and I also valued the opportunity to run the engine on the test stand and learn from William while I was there.

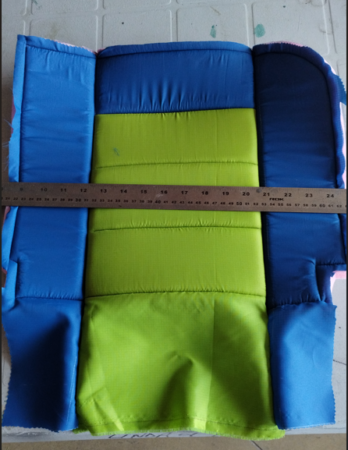

The amount of calendar time that passed during this whole process was greater than I originally thought it would be so I already had my LSA kit for 11 months by the time my engine ran. Of course this meant that when I returned home from Florida, I couldn’t resist installing the engine on the front of the airplane even though there is still a lot of other work to do on the fuselage. I got ahead of myself and installed the nose bowl to the prop flange, but now I need to go back and install the boot cowl before I can complete the cowling. The typical engine cowling used with the Corvair engine is very similar to the standard Bearhawk cowling. William Wynne sells a fiberglass nose bowl sized for the Corvair engine and then a sheet metal cowling is fabricated to go between the nose bowl and firewall with doors that open for easy pre-flight inspection.

Besides providing parts for converting Corvair engines, William Wynne provides education about the engine. Not just how to build the engine, but also how to own, operate and maintain the engine. I referred to a conversion manual that William sells, but there is also a Maintenance, Operations and Procedures manual that helps you through the flight test period and developing a POH for your aircraft. The support that William provides and the Corvair community that exists are a big part of why I decided to use a Corvair flight engine. I think there are some similarities between the Corvair community and the Bearhawk community in that I believe both draw more of the old school type homebuilders than you find in some of the other homebuilder circles.

For those of you who are interested in more details about the Corvair flight engine in general, I’ve listed some information below that largely comes from William Wynne’s website, Flycorvair.net.

More about the Corvair:

The Corvair is a General Motors designed engine, manufactured by Chevrolet. 1.8 million engines were built in the Tonawanda, NY engine plant between 1960 and 1969. The Corvair has been flying on experimental aircraft since 1960, and William Wynne has been working with them as flight engines since 1989.

Configuration: The engine is a horizontally opposed, air-cooled, six cylinder configuration. William only promotes its use as a simple, direct drive power plant. The engine configuration is very similar to Lycomings and Continentals.

Displacement: The engine is effective without a gearbox or belt drive because it has a comparatively large displacement. William supports versions that are 2700, 2850, 3000 and 3300cc. The smallest of these is twice as big as a Rotax 912. The 2850cc is very popular because it sits in a sweet spot for performance and value.

Power: The power ratings for these four displacements of Corvair flight engines are 100hp, 112hp, 116hp and 125+hp at 3000 rpm.

Weight: The 2700cc engine weighs 225 lbs ready to run.

This is effectively the same as a Continental O-200. It’s installed weight is 35 lbs more than a 912 Rotax, 25 lbs more than a Jabiru 3300 and 40 lbs lighter than a Lycoming O-235. 2850cc and larger Corvairs are slightly lighter than 225 lbs because the cylinders weigh about 5

lbs less. 3300cc Corvairs also use a billet crank which saves another 4 lbs. Aluminum pushrod tubes can be used on any of the engines to save another 1 lb.

Reliability: From the factory, the Corvair made up to 180 hp in the car and turned more than 5500 rpm. The flight engine is reliable and long-lasting because it is only operating at 55% to 70% of these levels. Conversion engines that run at the car’s red line rpm historically have short lives and cooling issues.

Cooling: The Corvair has a factory cylinder head temp limit of 575F. This is the highest limit on any mass-produced air-cooled engine ever built. The engine is also the first mass-produced turbocharged car. GM engineered the engine to have excellent heat tolerance and heat dissipation. In aircraft the engine typically runs at 325 to 350 CHT.

Parts availability: Every wearing part in the engine has continuously been in production for 5 decades. A high end Corvair conversion only has an original pair of cases, and oil housing and cylinder head castings. All other parts in the engine, including the crankshaft, are brand new. Many of the parts in the engine, like the lifters and valve train, are common to Chevy V-8s. There is no part availability issue.

Ignition: The fleet of flying Corvairs is about 500 aircraft. More than 90% of them have a dual ignition system built by William Wynne. His system uses two mostly redundant systems, one points based, the other a digital electronic system. The design has two of every part potentially subject to failure, but it utilizes one plug per cylinder. Six cylinder engines can fly on one cold cylinder, most four cylinder engines cannot. Plug fouling is unknown in Corvairs because the ignition system is 40,000 volts and uses a plug gap twice as wide as a magneto system.

Fuel: The Corvair can use either 100LL or automotive fuel. It is not bothered by ethanol in the fuel. When Corvairs were designed, car gas was a lot like 100LL; for the last 35 years every mile driven by Corvair cars was done on unleaded car gas. Many engines like 912s and modern car engines do not have exhaust valves that can withstand the corrosive nature of 100LL. William uses stainless and Inconel valves in Corvair flight engines.

Maintenance: The Corvair is low maintenance. The heads never need re-torquing. The valves have hydraulic lifters and never need to be reset or adjusted. William dislikes the term “maintenance free” because it implies a “no user serviceable parts inside” disposable appliance mentality. The Corvair is a solid, robust machine which holds its adjustments, but his program is aimed at teaching builders to be self-reliant owners.

My donor car:

Engine removed from car

Engine after disassembly

Bottom end as it returned from SPA

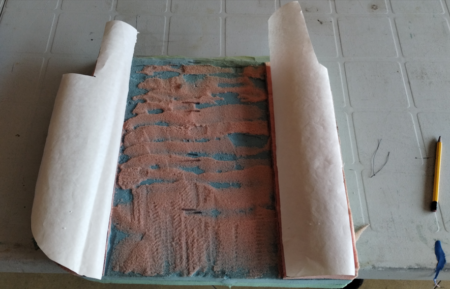

Bottom end after adding rear oil case, masking and painting

Masking removed and harmonic balancer added to rear of engine

Prop hub and ring gear added to the front of engine

New cylinders painted

Now at William Wynne’s shop in FL. Rods, pistons and cylinders installed.

Showing off my Bearhawk gear

Engine is repositioned to install the head from the top and then rotated to install the second head from the top as well.

Second head now installed and engine moved to the vertical stand

Valvetrain now installed

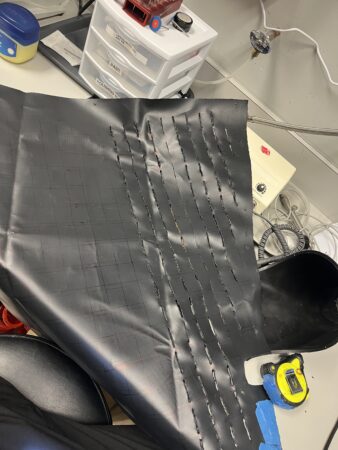

Ready to install oil pickup screen and oil pan

Oil pan now installed

Engine has moved to the test stand. Top cover, starter and oil filter housing now installed. Drip trays mounted on heads to catch oil during pre-oiling process performed with drill motor spinning the oil pump.

Pre-oil is complete, valve covers installed, and cooling shroud added in preparation for test run.

And it runs!

Back in Kansas, engine is waiting to be mounted on my LSA.

Engine mounted with William Wynne’s engine mount. The Corvair uses a bed mount.

20A alternator now installed.

Nose bowl installed. This nose bowl is designed to use the 13″ spinner from Van’s Aircraft.