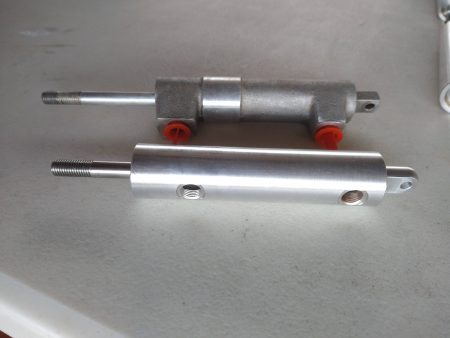

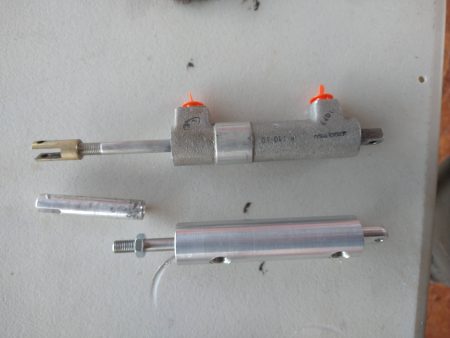

New Brake Master Cylinders Designed by Bob

Installing Aileron and Flap Hinges

Builder Update from Ken Frahm in Alaska

New Bearhawk Patrol Underway in Grassland, Alberta, Canada

LSA Builder Check-in From Tim Weaver, N2227T

Richard Eberlein’s Bearhawk 4-Place ZK-RJE

Original Scanned PDF Version of 2021 Beartracks Newsletters

Bob’s 2021 Picnic, Taxi Tests for the Electric Ultralight

A Bearhawk Time Machine – Flying to a Remote Test Site in California

Source: 2021 Q4 Beartracks, Russ Erb

You’ve heard it before—“Airplanes are Time Machines”. Usually this is in reference to airplanes being faster than other forms of transportation, able to get you to your destination quickly and allow you to get more “stuff” done in a particular time. For the purposes of this discussion, however, I’m thinking more along the lines of H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine, where my Bearhawk Three Sigma took me back in time to a set of events in my Dad’s history that actually took place before I was born. You may have done a similar thing—someone told you about an event of significance that happened in the past. Later you happened to visit the location of said event and tried to imagine what it was like to have been there. But what do you do if the location is essentially inaccessible? To bring you along on this journey of mine, let me first take you back in history to the events in question.

Piasecki H-21C Hover In-Ground Effect Flight Testing

Lee (Dad) and Alice (Mom) had just returned home from their honeymoon in 1954 when my Grandfather (Mom’s Dad), the local letter carrier, handed Dad a letter from the US Air Force telling him it was time to go on active duty to serve his ROTC commitment. He was sent to Edwards Air Force Base to become a Flight Test Engineer (FTE), a job I would later adopt for a full career.

One of the projects he was assigned to was flight test of the Piasecki H-21C Shawnee helicopter, more commonly known as the “Flying Banana”, even though it wasn’t flown by Gru’s minions.

Above: Alice and Lee at the Armed Forces Day Open House, 21 May 1955, standing in front of his H-21C flight test helicopter. Lee is holding my older brother who is two weeks old

Below: Piasecki H-21C Shawnee, powered by a Wright R-1820-103 radial piston engine

One reason helicopter performance testing is different is the strong influence of ground effect. While airplanes do respond to ground effect (better performance within one wingspan of the ground), the effect is not generally that significant. I do takeoffs and landings in my Bearhawk without any noticeable feeling that I have left or entered ground effect. Helicopters, however, are strongly affected

by ground effect, sometimes able to hover a few feet off of the ground in ground effect but unable to climb any higher. This was especially true of older piston engine helicopters, where the power plant weight was high and the payload was very limited. In this case flight could only be established by flying forward in ground effect (or on a runway) until translational lift reduced the power required enough for flight.

Airplanes can generally be tested for predicted takeoff and climb performance at high altitudes simply by doing level accelerations and climbs at higher altitudes, thousands of feet above the ground, because the difference caused by ground effect is so small. For helicopters, this doesn’t work at all, and tests have to be run in ground effect at high density altitudes.

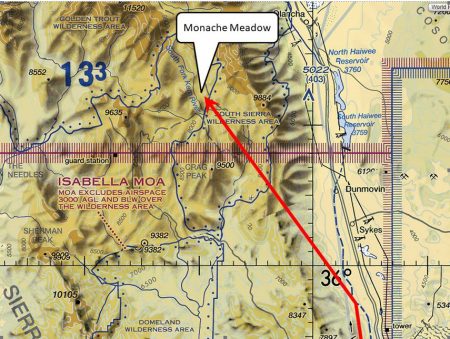

Of course, this requires having a suitable airport, or at least terrain, available for testing at high elevations. The elevation of Edwards AFB is only 2311 feet, which isn’t exactly high. One high altitude site available within a reasonable distance from Edwards AFB is Big Bear Airport at 6752 feet elevation. Big Bear is noted for its ski resorts and alpine climate, as well as Big Bear Lake. Dad said that they did some helicopter testing at the Big Bear Airport. I have even been involved with a flight test project flown at Big Bear to simulate the elevation of the US Air Force Academy. For really high density altitudes they would go to a place called Monache Meadow (type “Monache Meadow California” into Google Maps to see where it is located). This area was well up in the Sierra Nevada mountains with elevations of 7600 feet and higher. There was a large open area without trees or mountain peaks in the way, making it ideal for helicopter testing only 79 miles from the base and inside the MOA/Restricted Area.

Above: Dad’s Test Pilot, Gus Vincenze, with the H-21C, possibly on Monache Meadow.

Below: Flight Test planning in the field, possibly on Monache Meadow. Lee is in the white coveralls on the right. Then again, they may just be shooting craps…

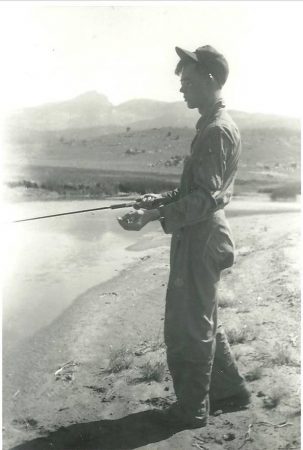

Below:From his own annotation written on the back of the photo “1/Lt Lee Harvey Erb testing the H-21C helicopter at Monache Meadow, CA. 7600 foot elevation. June 30, 1955”. Note that his first son is less than two months old at this point. This is probably at the South Fork of the Kern River

Dad told me the story that the Air Force was very welcome at Monache Meadow. A man who lived there had a daughter who was very sick and needed to get to a hospital. Unfortunately, Monache Meadow is only accessible by 19.5-mile Monache Meadows Jeep Road that is rated as “moderate” and 4WD recommended—not exactly ambulance accessible. Instead, he called the Air Force requesting assistance. The Air Force sent an H21C up to Monache Meadow, but the density altitude was so high that the helicopter could not take off with the pilot, the patient, and the crew chief on board. Therefore, the crew chief got off the helicopter, and the pilot flew the patient to a hospital. The crew chief waited at Monache Meadow until the pilot could return with the helicopter to retrieve him. Needless to say, the father was very appreciative and gave great support to the Air Force whenever they were there.

Road Blocks In The Space-Time Continuum

My Dad had told me these stories long ago. From several of his visits while I worked at Edwards AFB, I had managed to piece together much of his history in my mind, including locations where he had worked. Part of the problem was that he was at Edwards at the time that Edwards was transitioning from what is now called “South Base” to what is now called “Main Base”. If you look at an airport diagram of KEDW, Chuck Yeager, Jack Ridley, Bob Cardenas, and Bob Hoover did not take off on Runway 23L-5R, the current main runway of Edwards AFB, on 14 October 1947 to break the sound barrier. That runway didn’t exist yet. They took off on Runway 25-7, which at the time was labeled 24-6.

The movie Toward the Unknown was shot around this time and helped with understanding the previous base configuration. I had also flown to Big Bear multiple times, so I knew where that was. Monache Meadow was another problem, though. Dad couldn’t really remember exactly where it was, other than “up north in the mountains”. Adding to the problem was the way he said the name, which sounded like “Menanche Meadows” to me, which didn’t show up on any of the maps (this was before Google Maps). For that matter, it isn’t called out on the sectional or any other aeronautical charts. I often wondered if that was just a nickname for the location, named for someone who lived there and not officially recognized by the US Geological Survey. When Dad passed away in February 2020 I figured

that I would never know.

Somehow recently I stumbled across something that mentioned “Monache” and I wondered if it could be related to what I was looking for. After some Google searching, I found Monache Meadow in about the expected location. It fit the description of a high altitude plain in the mountains within the Edwards flying area, empty of trees and obstacles. As mentioned before, I couldn’t drive there since it was way up in the mountains and I didn’t have a suitable vehicle. I could possibly fly over it, but there were very high peaks around it. I would have to plan carefully and watch out for high terrain and strong winds that could cause turbulence.

Going Back In Time

I asked Aaron, a coworker and student pilot, if he was interested in some Bearhawk flying. He had been waiting for this offer for a long time, and said he was interested in looking at some wooded mountain terrain near Tehachapi for an upcoming project. I agreed, and asked him if he would also be interested in a high altitude overflight of Monache Meadow. He agreed, which was great, because I needed a second crew member to do the overflight safely.

On 20 November 2021 the sky was clear and winds at altitude were light. Flying up the narrow VFR General Aviation corridor between the Sierras and the China Lake Restricted Area, we approached at an altitude of 10,500 feet, which near the mountains still seemed low. Because of the high peaks just East of Monache Meadow, we turned in early over a lower ridge to stay over relatively lower terrain, as shown by the red arrow.

Over the mountains I drifted up toward 11,000 feet as the ground still seemed close. I handed my phone to Aaron and asked him to take “a whole mess o’ pictures” while I made two right hand turns over the meadow. I knew from previous experience that it is dangerous to try to fly turns over a point on the ground at low altitude while looking at that point on the ground and studying it. It’s even worse if you are trying to take pictures of that point on the ground. The problem is that while staring at the ground it is very easy to lose your pitch control, either descending without your knowledge or slowing to a stall. That’s why I had Aaron take the pictures while I divided my attention between maintaining altitude, not running into high terrain, and occasionally glancing at the ground.

While it looks flat and possibly landable from this altitude, I wasn’t interested in biting off that much risk, especially at these high altitudes. It appeared completely deserted. Even so, it was very fulfilling to see the place from altitude. Now I knew where it was, and I could imagine my Dad down there, struggling with an underpowered helicopter trying to collect flight test data for the good of the Air Force. The Bearhawk had taken me there to feel a connection to the work that my Dad had done which inspired me to follow my career. The best part is that I can go back there again.