Source: 2024 Q3 Beartracks, Paul Minelga

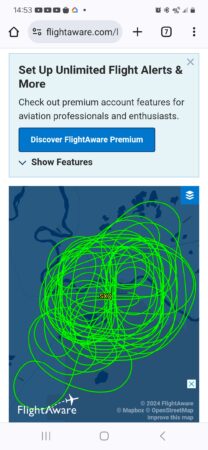

Here’s an update of N907PM’s flights, up to 28.2 hours on the Hobbs. Well, there isn’t much to update! This may be shocking to some, but completely logical to me, so let me walk through the hours from first flight to present.

I already went over my first flight in the previous Beartracks article and YouTube video, so no surprises there. So what happened next? Extensive testing of the flight envelope? Figuring out the handling characteristics of my Bearhawk? Multiple stalls, turns, simulated engine failure, full-flap landings? Nope. None of that…well, almost none, but I will explain why and you can critique as you wish.

The first flight was certainly an exhilarating experience. It was the first date with a new machine, flying at the upper range of its engine and airframe performance envelope. The excitement of not knowing which sounds were normal and which sounds could be the beginnings of a catastrophic event was to be experienced, as only one can on a first flight! Well, 1.3 hours later proved the airframe and engine were up to the task of at least one safe takeoff, flight and landing. But the question remained: What’s next? I have a considerable amount of time and money invested in the engine and I want to break it in as best as possible. The EAA test flight checklist doesn’t allow for this scenario. Since the aircraft didn’t offer up any surprises and it is a proven design, my focus on the subsequent hours were focused on engine operating parameters and a proper break-in. In other words, I ran the engine hard. Running hard meant no air work, no slow flight, no series of stop and go landings, no shock cooling, all in the name of engine break-in.

At 5 hours I did my first oil change, and it was necessary! The oil looked like metallic graphite paint! I cut apart the oil filter and thankfully it didn’t yield any unwelcome surprises. Along with the oil, the oil filter just showed minute evidence of a LOT of new moving parts in a powerful internal combustion engine getting to know one another. I even pulled the oil screen in the sump. Fortunately, there weren’t any pieces with part numbers trapped in its mesh. Oil was still being consumed, or blown overboard, but I still don’t know where this engine’s “happy spot” is on the dipstick…every engine has one. So more flying is in order….a lot of flying…within gliding distance of my home airport, until about 10 hours. After that, I did a flight with the last 30ish minutes using a modified EAA test flight checklist by doing stalls and exploring trim changes with different flap settings. I also did a full-power go-around at altitude with three notches of flaps to check if I could overcome the sudden initial trim change. I did.

After that 10ish hours without an engine failure I figured it was time to spread my wings a bit and do a little cross country, at full power of course. I was flying in familiar territory. In my beautiful part of Alaska there are a BUNCH of airstrips available in case of an unfortunate event. Almost all are private, but I have yet to meet anyone that would not welcome a pilot in immediate need of a short, semi-flat surface. So my next 15 hours were spent doing cross country flights, at altitude, at close to full power. At 25.4 hours it was time for a another oil change and a good look over of the airframe. In addition to the oil change, I did a mini condition inspection as most of the important parts on the airframe and controls are hidden behind panels and can’t be seen on a preflight. I built a tail stand and calibrated my oil dipstick in the 3pt attitude and verified the factory stamped level attitude markings.

So what are my takeaways and what did I learn? First and foremost I always did a good preflight and a very thorough post-flight after every flight. On one post-flight I discovered the inlet fitting of the oil cooler started leaking. Everything stopped until it was fixed. I also maintained a meticulous log of the engine parameters. Even at the top end of the performance envelope, flying in circles can get pretty boring. Every flight I recorded the OAT, engine oil temperature, oil pressure, each cylinders EGT and CHT (Number 2 has always been my hottest), fuel flow, volts and amps. During my cross country flights I experimented with how minor trim settings affected level flight and always tried to keep my altitude within 50 feet of my target altitude. BTW, my BH can be trimmed to fly hands-off in smooth air, no heavy right wing as some have experienced. I feel very fortunate in that area. I also have a real-time CO detector in the cockpit and I recorded those readings as well. I never saw more than 1 PPM in level flight and 8 PPM maneuvering. I also took note of the differential between the level of the fuel tanks after refueling. I always flew with both tanks selected and never had more than 1 ½ gallons differential between the two at refueling.

One thing that took me off-guard a bit was making the transition from fabrication mode to maintenance mode. I built this thing, now I have to maintain it. It’s a completely different set of skills! I started a list of deferred maintenance items to “fix” during my next condition inspection. They are all minor, but should be resolved.

Now that I am satisfied that the engine is broken in and the aircraft doesn’t exhibit any control anomalies, I will start and complete the EAA flight test checklist. I feel it is very important to do the methodical testing and documentation of the aircraft. But, like I said before, this is a tried and true design and the first few hours didn’t exhibit any builder-induced surprises, so I was comfortable in getting the engine properly broken in before going any further. As an aside, I legally took up my first passenger the other day…my wife! The day was stunning. It was completely clear, light wind and the fall colors of the birch and aspen against the turquois blue of the Kenai River were amazing. Even Denali (formerly Mt. McKinley) was in full view in spite of it being over 150 miles away. “Don’t give in, don’t give up.” – Iwai Makoto

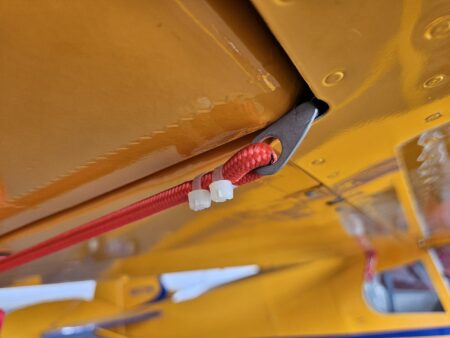

Control Locks:

I want to share what I made for the 4-place BH. Yes, they look almost identical to the Atlee Dodge gust locks because that’s where I got the idea from. I would have bought them from Atlee, but I wasn’t sure if the profile angle of the Piper aileron/flap matched the angle of the BH control surfaces. Also, the bungees holding the Atlee locks in place wrap around the lift strut of the Piper. That isn’t an option for the BH as the lift strut is way out of alignment with the aileron/flap intersection. I looked at ways to attach a bungee and almost settled on drilling a hole in the bottom of the wing somewhere close to the edge and installing a small eye bolt. I spent a lot of time just thinking about options when saw a little hole in the wing that is created by a stiffener that is riveted to the trailing edge of the flap pocket. I tried out different diameters and lengths of rods and found one that slid in and out without any trouble.

I made the pins and the eyes welded to the end of the pins out of stainless steel so they wouldn’t rust. I made the locks themselves out of some scrap .060 5052 that I had in my now vacant shop and glued some neoprene strips on the surfaces that contact the fabric. A couple of red bungees, flagging and some zip ties later I have a set of gust locks!

I have a set of Air Gizmos gust locks that I was using for the flaps, but I had to still tie the stick back. Also, there were a couple of times I found the gust lock on the ground when it had worked itself loose. The Air Gizmo lock works great as long as the surfaces are close to parallel. So instead of buying another set for the elevator, I made these and am now using the ones I had for the flaps on the elevator. Now everything is tight and I don’t have to use the seat belt to tie the stick back.

Tail Lift: